The Real Problem Isn’t Gentrification—It’s Exclusion

How A Broken Land Use System Protects the Status Quo In Some Places But Not Others, Fueling Gentrification and Limiting Upward Mobility

Knoxville isn’t the same as it once was. Once a bastion of affordability, the region has seen housing costs skyrocket, vastly outpacing the growth in earnings. The pandemic accelerated this trend—spurring an influx of new residents from high-cost areas that, combined with record low interest rates, boosted housing demand far beyond what the market could readily absorb.

Regardless of how we got here, one thing is clear: the chronic shortage of housing is why prices continue to climb upward. Affordability has been steadily deteriorating for more than a decade, exerting enormous pressure on the working families, and a broken land use system continues to constrain new supply—especially in the places where people most want to live. The consequences have become impossible to ignore.

The chronic shortage of housing and erosion of affordability isn’t just a social or moral concern. It’s a structural problem with broad economic consequences for Knoxville's future.

The High Cost of Not Enough Housing

Since at least the New Deal era, when the federal government helped birth the 30-year mortgage, Americans have viewed housing as both shelter and strategy—a place to live and a mechanism to build wealth. But in cities across the country, and increasingly in places like Knoxville, that foundational promise is increasingly out-of-reach for the typical family.

Part 1: Affordability

Deteriorating affordability is most obvious consequence of too little housing.

Knoxville has consistently ranked among the top U.S. metro areas for home price growth in recent years, with inflation-adjusted home prices increasing by 60% from 2019 to 2025, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.

A recent study by the National Association of Realtors and Realtor.com demonstrates that, while for-sale inventory has largely returned to pre-pandemic levels, there is still a significant affordability gap. As of March 2025, an annual income of $75,000 was enough to afford just 13.2% of the homes listed for sale in Knoxville—meaning more than half of households can afford less than 1/5 of homes listed for sale. In a balanced market, an annual income of $75,000 would be enough to afford 50% of listings.

Among the most jarring examples of our broken housing market is its disproportionate impact on the working class. In Knoxville, as in many mid-sized metros, the affordability crisis hasn’t just priced out the lowest-income families. It has also priced out the types of workers that our communities cannot function without—firefighters, police officers, teachers, nurses.

According to a similar analysis from 2023, the starting salary for a Knoxville Police Officer was enough to afford just 2% of homes on the market. The message is implicit but unmistakable: even those tasked with safeguarding and educating our community can no longer afford to live in it.

(Note: Percentage differences between the two charts reflect varying assumptions. The first chart, from NAR, uses 2025 data and variable down payment scenarios. The second chart, created by the author, uses 2023 data and assumes a fixed 5% down payment when calculating affordability thresholds.)

One of the clearest lenses through which to view Knoxville’s affordability crisis is deceptively simple: the price-to-income ratio. By comparing the median cost of a home to the median household income, the PTI ratio metric strips away the noise of interest rate fluctuations and demand-side subsidies, offering a more durable measure of affordability. When home prices rise significantly faster than incomes, the ratio reveals the strain that markets place on ordinary buyers, especially those trying to purchase their first home.

In healthy markets, the price-to-income ratio typically hovers between 2.2 and 3.5—a level where a middle-class household can reasonably aspire to own a home without financial strain. But when the ratio exceeds 4.0, it signals growing affordability challenges.

Knoxville’s housing market for decades maintained a sense of balance, avoiding the boom-bust cycle that is common in many other cities, with the region’s price-to-income ratio hovering around 3.3 from 1980 to 2015.

But that equilibrium began to shift in the mid-2010s, with the ratio inching up to 3.8 by 2020. Then came the pandemic—and with it, an unprecedented surge. By 2024, the price-to-income ratio climbed to an all-time high of 5.1. The spike was not driven by a speculative bubble or sudden collapse in wages, but by a deeper, structural imbalance: too many people chasing too few homes.

As a result, nearly half of all renters in Knoxville are considered cost-burdened—which according to the federal government is defined as spending 30% or more of one’s income on rent—and first-time homebuyers have nearly become an endangered species, forced to delay homeownership and, with it, years of forgone housing wealth.

Part 2: The Geography of Opportunity

At a macro level, the housing shortage is broad-based. Aside from long-time homeowners with fixed mortgage payments, few families have been able to avoid the dramatic rise in cost-of-living. But the housing gap is most severe in the places people most want to live—high-opportunity neighborhoods with strong schools and access to good jobs. This geographical disparity is especially important because where a child grows up can profoundly shape their future.

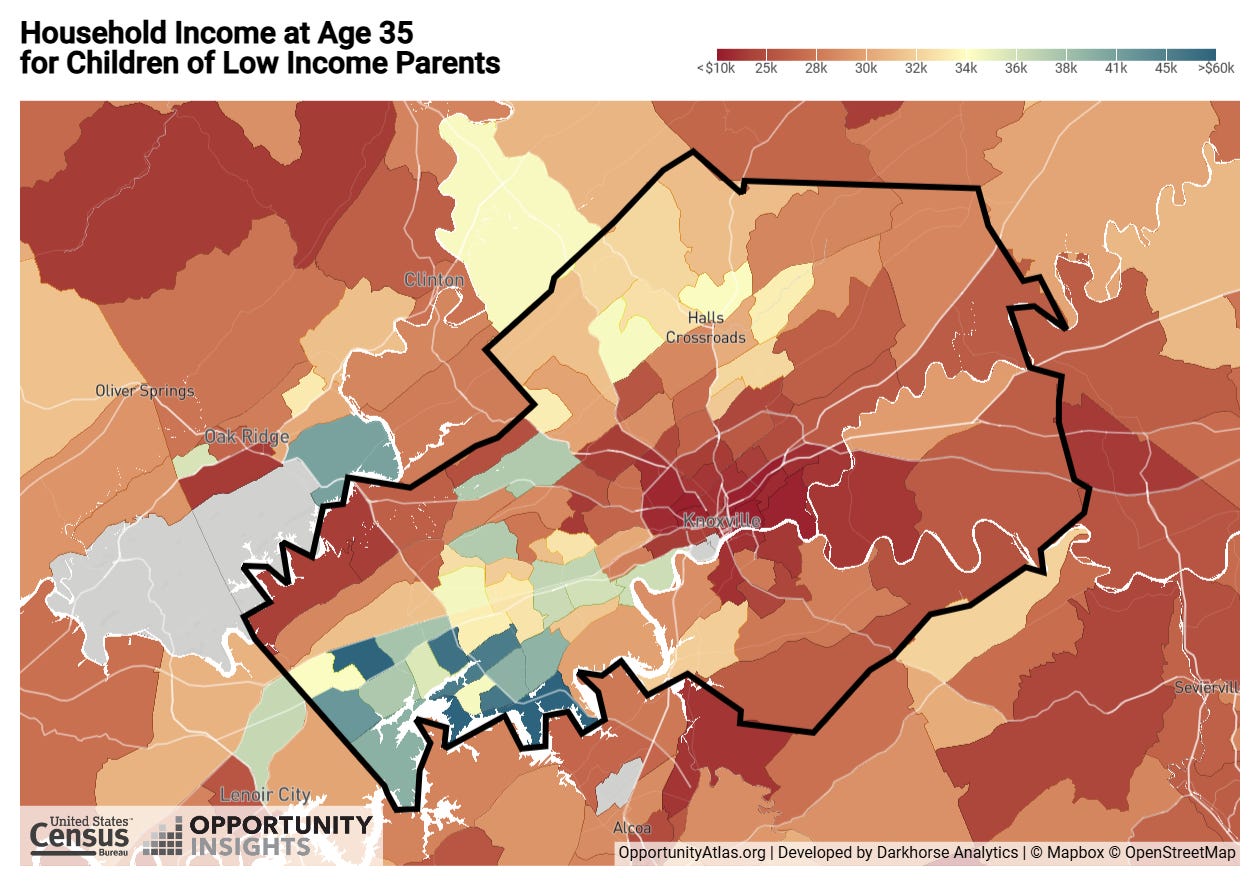

Groundbreaking research by economists Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Nathaniel Hendren shows that economic mobility—or one’s ability to improve their economic status over time—is deeply influenced by place, social connections, and access to opportunity. Drawing on anonymized IRS and Census data, their team tracked over 20 million children born between 1978-1983 and linked their adult outcomes—such as income, education, and incarceration rates—to the neighborhoods where they grew up, allowing them to explore how much a person’s life outcomes are shaped by the economic circumstances and neighborhood they were born into.

The results of their research are as uncomfortable as they are undeniable: opportunity is not evenly distributed. It’s clustered in specific neighborhoods—often the very ones that use zoning and land-use restrictions to prevent new development.

In the Knoxville area, for example, low-income children who grew up in Parkridge had an average household income of just $17,000 by age 35. In contrast, their peers who grew up in Farragut averaged $53,000—despite coming from families with similar economic backgrounds.

These disparate outcomes are even more pronounced for males from the lowest income households. For those who grew up in Parkridge, only 48% were employed at age 35. By contrast, among male children from similar economic circumstances but who instead grew up in Farragut, more than 95% were employed by age 35.

And the disparities aren’t limited to income. By age 35, low-income children who grew up in Parkridge were less likely to be married and almost 6 times as likely to be incarcerated than low-income children who grew up in a high-income, high-opportunity suburb like Farragut.

Even the high school you attend can shape your future by influencing your social network. Chetty’s more recent work found that communities where low- and high-income people interact more frequently tend to produce better outcomes for low-income children. These cross-class friendships, often formed in schools, are among the strongest predictors of upward mobility. Children embedded in stronger networks are more likely to have access to internships, jobs, and support systems that provide the stability and resources to take productive risks, such as pursuing higher education or starting a business.

Consider the contrast between attending different high schools across Knox County. At Austin-East Magnet High School, Chetty's data shows that low-income students have social networks in which just 19.7% of their friends are high-income. At South-Doyle High School, that figure rises to 31.1%. And at Bearden and Farragut, it jumps to 71.2% and 76.5%, respectively.

These disparities in exposure to opportunity and social capital reinforce the importance of ensuring that more families can access high-opportunity neighborhoods, if they so choose. Yet, opposition to new housing—and especially the types of housing that are affordable to working class families—is strongest precisely in the areas where it would produce the most benefit. High-opportunity neighborhoods often have the most restrictive zoning, the most vocal resistance to development, and the highest barriers to entry—effectively shutting out lower- and middle-income families who stand to gain the most from living there. In other words, the very neighborhoods best positioned to expand opportunity have proven to be the least willing to share it.

Part 3: How Exclusion Amplifies Gentrification

New development—whether residential or commercial—tends to face the strongest opposition in high-income, high-opportunity areas. That resistance creates a powerful incentive for developers to concentrate their efforts elsewhere, in neighborhoods where public pushback is less organized or less intense.

It’s not hard to see why. Public opposition creates uncertainty, delays timelines, and can ultimately sink a project altogether. For developers, every month of delay means higher carrying costs and greater financial risk. And if a project is denied, all the time and money invested are lost.

The result is a perverse but predictable dynamic: development is steered away from high-opportunity neighborhoods—where access to good schools, jobs, and amenities is greatest—and funneled instead into lower-income areas, where public opposition is weaker but the risk of displacement is higher. “If you’re in a wealthy neighborhood, and they’re educated, they’re going to be harder to deal with,” one small developer told Yoni Applebaum for his book Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity. “If you’re in a poor neighborhood that’s less educated, they’re probably going to be easier to deal with.”

This dynamic is one of the most overlooked aspects of local housing policy. When new homes can’t be built in desirable areas because of neighborhood opposition, demand doesn’t disappear—it shifts. Buyers and renters compete for a limited number of homes in nearby, more affordable neighborhoods. As competition intensifies, so do prices, and longtime residents—often with fewer financial resources—face a greater risk of being displaced.

Ironically, the very policies meant to “protect neighborhood character” in affluent areas accelerate change in the neighborhoods least equipped to absorb it. And the net effect is stark: we preserve exclusivity at the top while amplifying instability at the bottom. We make it nearly impossible to add housing where demand is highest, while concentrating new development in the places most vulnerable to the negative effects of change.

This is how exclusion fuels gentrification. By walling off high-opportunity areas from new housing, we don’t stop growth—we just redirect it to the path of least resistance. The neighborhoods with the most to lose become the ones forced to change and, in doing so, our land use system quietly but powerfully entrenches inequality. It rewards resistance and punishes openness. It treats stasis in affluent areas as virtue and change in poorer ones as inevitability.

That’s why, if we truly care about preventing displacement and expanding opportunity, the solution isn’t to halt growth—it’s to share it.

A Better Path Forward

Knoxville’s affordability crisis isn’t inevitable. It’s a policy choice. And like any policy choice, it can be changed. For too long, we’ve accepted a land use system that allows a handful of neighborhoods and public hearing participants—which research shows tend to be older, wealthier, and more opposed to housing development than the general public—to decide where and how much housing gets built. The result has been a deeply unequal status quo where high-opportunity neighborhoods remain frozen in time, while lower-income communities shoulder the full weight of growth, gentrification, and rising costs. A better path forward will require rebalancing that equation and embracing a pro-housing agenda that removes arbitrary constraints on new construction and ensures growth is equally distributed.

The aim of policymakers shouldn’t be to relocate people. It should be to build a land use system that empowers individuals from every background to access opportunity—and to choose the kind of housing that best fits their needs. Growth, after all, isn’t the problem. Exclusion is. Gentrification determines who moves in; exclusion decides who never gets the chance. Growth will happen somewhere. The question is whether we allow it only in places where people lack the power to say no.