A Pro-Housing Agenda For Knoxville

5 Zoning Reforms That Can Expand Housing Opportunities and Lower Costs Across Knoxville

Knoxville is growing—and anyone who’s lived in the area for more than a few years can feel it. Home prices and rents have vastly outpaced income growth, traffic congestion is worse than ever before, and new subdivisions seem to appear at every turn. And growth and development has become the defining issue for nearly every aspiring political candidate.

The wave of growth isn’t exactly new. It began in earnest around 2015 but accelerated to unprecedented levels in the wake of the pandemic, as rapid in-migration and economic growth made Knoxville one of the nation’s fastest-growing housing markets. The growth in population, tourism, and economic activity has undeniably brought challenges—especially around housing affordability and infrastructure—but it has also been the key driver of many positive trends, including expanded air service with the entrance of Southwest Airlines and the arrival of new restaurants and national brands like Nordstrom Rack, Whataburger, and Topgolf. Indeed, growth has delivered conveniences, choices, and opportunities that would not have materialized if Knoxville’s population and economy had stayed flat.

Today, things have slowed down. Inflation ravaged the U.S economy for more than three years and is still running hot. More and more companies are reversing their pandemic-driven shift to remote work, which was a key driver of the region’s growth in recent years. But even as Knoxville and the broader United States faces economic headwinds, two realities remain: (1) Knoxville isn’t going to stop growing anytime soon, and (2) we weren’t prepared for the growth we’ve already experienced.

East Tennessee has long been immune to the boom-bust cycle that afflicts many other cities when economic conditions waver. But that resiliency, historically, stemmed from a well-supplied, affordable housing market that made it easy for families to settle down and invest in the community. Over the past decade, however, housing supply has fallen far behind demand and the result has been soaring costs, which have left many families struggling to make ends meet.

That’s why its time we embrace a pro-housing policy agenda. It is about more than just housing—it is about opportunity, affordability, and ensuring that Knoxville remains a place where people of all incomes can thrive. A logical starting place is to reform our zoning laws, which compound the affordability crisis by placing arbitrary constraints on new construction and driving up prices. These rules determine not only how much housing can be built, but where—and whether Knoxville is a place of economic opportunity or a place where only a few can afford to stay and thrive.

So, here’s what a pro-housing agenda might look like.

Allow Duplexes By-Right in Every Neighborhood

Duplexes were once a vital and familiar part of American neighborhoods, offering smaller housing options that are naturally more affordable for working families, retirees, and young professionals who prefer not to stretch their budgets for additional space they don't want or need.

Today, however, duplexes are often prohibited or subject to discretionary approval processes in areas where single-family homes are allowed by-right.

This regulatory disparity is difficult to defend.

Consider two homes, each with 3,000 square feet of space. One is a single-family home with four residents; the other is a duplex with two modest units, each housing two people. These structures have the same footprint, the same number of occupants, and the same impact on roads and infrastructure. The only real difference is a second front door. Yet one is permitted without question while the other is subject to intense scrutiny.

Such inconsistencies in zoning policy raise important questions: why do we regulate nearly identical structures so differently? Why are duplexes viewed as disruptive or undesirable, even when they blend seamlessly into existing neighborhoods? If there is no demonstrable difference in impact, what is the policy rationale for restricting them?

Zoning should protect against tangible harms—not enforce the subjective aesthetic preferences of surrounding homeowners. Where no tangible harm exists, government shouldn’t stand in the way. Allowing duplexes by-right in all areas currently zoned for single-family housing would constitute a modest but meaningful step toward expanding housing choice and improving affordability, especially in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

Allow duplexes by-right in all zoning districts that permit single-family housing.

Make Accessory Dwelling Units Easier to Build

Accessory Dwelling Units, known as ADUs, are small secondary dwellings on the same lot as a primary residence, often referred to as a backyard cottage, granny flat, or garage apartment. These housing types are ideal for aging parents, young adults, or renters seeking modest, affordable housing—oftentimes neighborhoods they couldn’t otherwise afford.

In Knoxville, however, ADUs remain relatively uncommon due to restrictive zoning and regulatory barriers. This is significant because regulatory change can have an outsized impact on whether homeowners feel empowered to add these types of dwellings. Cities across the country have demonstrated that once barriers are lowered—such as reducing parking mandates, allowing ADUs by-right, or simplifying design standards—construction of ADUs increases substantially.

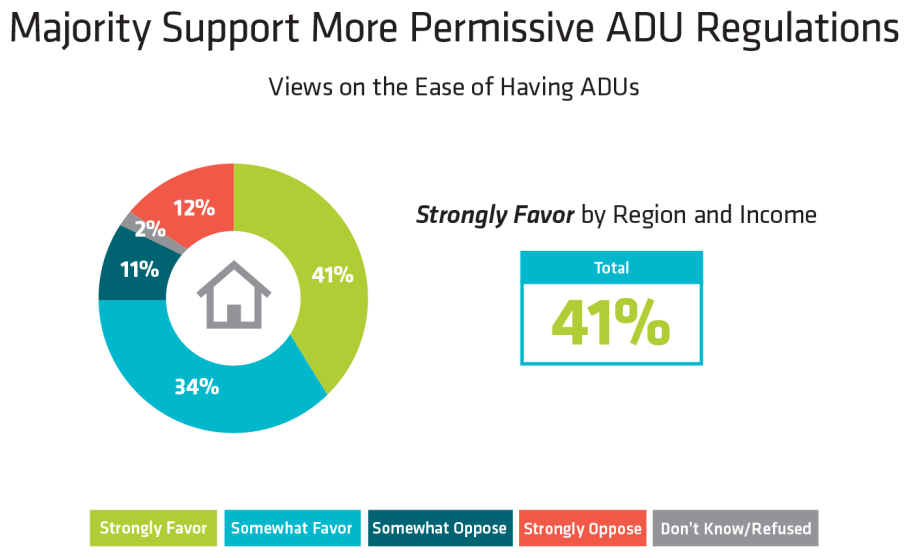

Unlike many other housing reforms, ADUs enjoy broad public support. Approximately 75% of Knox County residents indicating they favor more lenient regulations to make it easier to build ADUs, according to a poll released by East Tennessee Realtors. This makes ADUs not only an economically sound solution but also a politically popular one—a rare combination in today’s often polarized debates over growth and development.

The benefits extend beyond affordability. ADUs allow families to stay together across generations, provide seniors with opportunities to age in place, and give homeowners a potential source of supplemental income. They also make more efficient use of existing infrastructure, since they add gentle density without requiring major new road or utility expansions. In other words, ADUs offer a low-impact way to expand Knoxville’s housing supply while preserving the character of existing neighborhoods.

It’s no surprise, then, that AARP has become one of the nation’s strongest advocates for ADU reforms. With America’s population rapidly aging, AARP highlights ADUs as a practical, community-based tool to help older adults remain close to family, reduce social isolation, and live independently for longer. For Knoxville, where both affordability pressures and an aging population are real concerns, ADUs represent a commonsense reform that aligns with both demographic needs and voter preferences.

Allow ADUs by-right in all residential areas—regardless of whether the primary home is owner-occupied or rented.

Reduce Minimum Lots Sizes or Start Regulating Lot Width

Reducing minimum lot sizes is one of the most effective ways to make housing more affordable. When zoning requires large lots, it forces each home to carry the cost of more land and, ultimately, driving up the price of every new unit. By contrast, smaller lot sizes allow more homes to be built on the same parcel, lowering the land cost devoted to each home and making entry-level housing more feasible for builders and buyers alike.

Lot size reform also helps expand the overall supply of housing. Large-lot zoning limits how many homes a community can accommodate, artificially constraining supply even as demand continues to rise. By enabling more homes on the same amount of land, smaller lot requirements make it possible for the market to better keep pace with growth, moderating price increases over time.

Alternatively, Knoxville could stop regulating by minimum lot size altogether and instead regulate minimum lot width.

Regulating by minimum lot width focuses on what actually matters for neighborhood character and infrastructure: the frontage along the street. Lot width determines how homes line up, how walkable a block feels, and how much street, sidewalk, and utility infrastructure is required. A 40-foot lot width, for example, still ensures consistent spacing and form, but it allows flexibility in how deep the lot is. That flexibility makes it possible to create more lots, lower the land cost per home, and deliver housing that’s affordable to more people—all without sacrificing the look and feel of the neighborhood.

Reduce minimum lot sizes in targeted areas and/or regulate by lot width instead of lot size.

Revitalize Knoxville’s Commercial Corridors

Many of Knoxville’s major corridors—from Kingston Pike to North Broadway to Chapman Highway—are replete with underused strip malls, vacant parking lots, and dilapidated buildings. These areas have a tremendous amount of potential and could, if redeveloped, greatly expand the region’s housing supply.

However, redevelopment along corridors is often stymied by rigid zoning rules that are designed to facilitate exclusively mixed-use development, with a combination of housing and ground floor commercial space. This type of development should be encouraged through tax incentives and other public support but not mandated in every case.

For pedestrian-oriented businesses to succeed, they need enough population density and foot traffic to support the higher rents of new commercial space. Yet most major corridors in Knoxville are bordered by low-density neighborhoods with little pedestrian activity, and some have virtually no nearby housing—or even basic pedestrian infrastructure. To make mixed-use development financially feasible on these corridors, zoning regulations should encourage higher residential density not only along the corridor itself but also in the adjacent neighborhoods.

Importantly, developers have strong incentives to build mixed-use projects when sufficient demand exists. Ground floor commercial space yields significantly higher rents than residential space and can therefore boost a project’s profitability. But when local consumer demand is lacking, commercial spaces sit vacant or must be leased at below-market rates to non pedestrian-oriented businesses.

This disconnect between regulatory expectations and market realities produces a lose-lose scenario: developers struggle, businesses fail, and residents miss out on the vibrant, walkable neighborhoods they want. That’s why, rather than demanding perfection, Knoxville should focus on practical progress—removing barriers to more housing near corridors and letting demand for walkable businesses grow naturally over time.

To jumpstart redevelopment efforts, local leaders (both in the city and county) should establish a corridor redevelopment task force composed of community members, planners, developers, and business leaders charged with identifying regulatory barriers and making recommendations about targeted reforms.

Eliminate Residential Parking Requirements

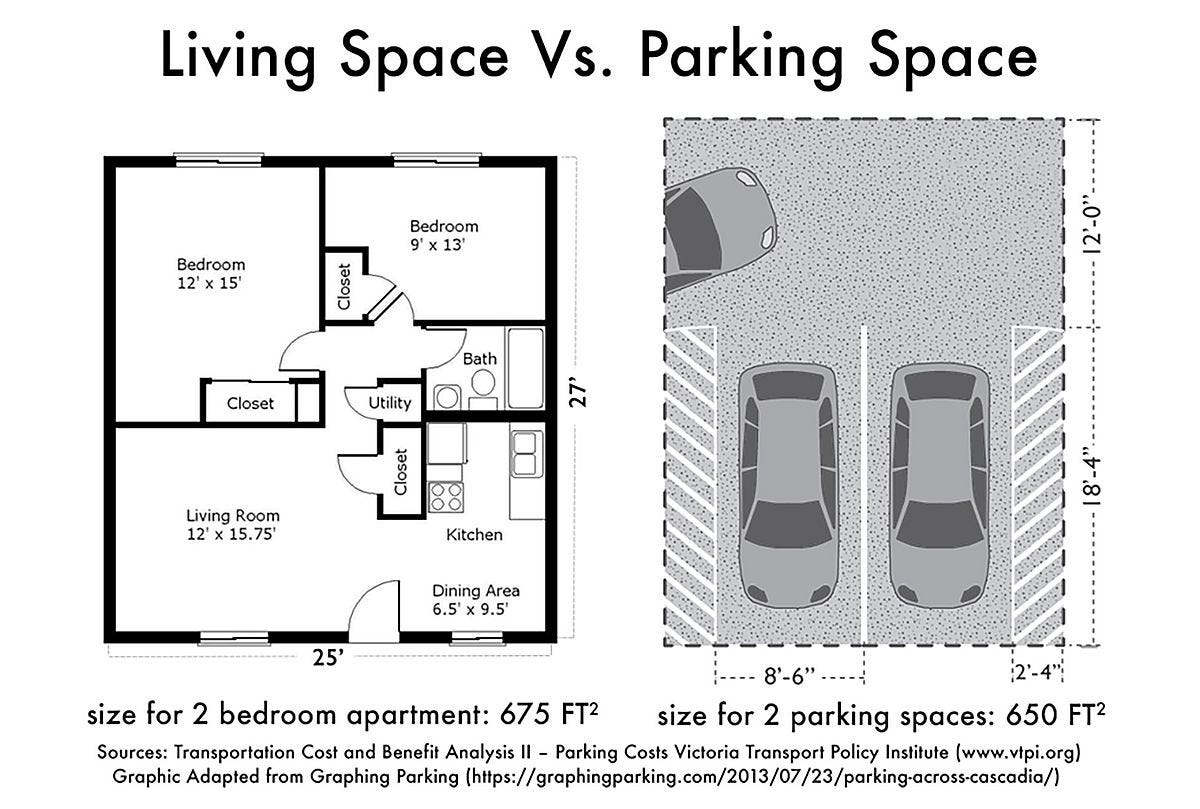

Residential parking requirements are another example of well-meaning but counterproductive policy. Mandating a minimum number of parking spaces per unit drives up construction costs, limits design flexibility, and discourages more efficient land use—especially in areas near transit, employment, and schools.

Numerous studies have shown that surface parking can significantly inflate the cost of building new housing, adding an estimated $5,000 per surface space (and probably more). In some cases, parking can make make up 10% to 18% of typical building development costs, creating a barrier to redevelopment—raising financial barriers to building new housing, especially in older neighborhoods where space is limited.

Worse still, research indicates that parking minimums are frequently set above actual demand. Developers are then forced to build more parking than residents actually use, with the added costs passed on to renters and homebuyers.

Eliminating parking mandates doesn’t mean eliminating parking. Rather, it means giving developers the flexibility to provide parking based on the specific needs of each project and the context of the surrounding area. In walkable neighborhoods or near transit, less parking may be needed; in car-dependent areas, more may be provided.

A one-size-fits-all mandate, by contrast, often forces trade-offs that harm communities—turning what could be a neighborhood park, courtyard, or additional housing into an underutilized parking lot. If we’re serious about affordability, we need to rethink parking policy as part of a more flexible and context-sensitive approach to housing and land use.

Reduce or eliminate mandatory off-street parking minimums for all new residential development.

Conclusion

The housing crisis is undeniably complex. Higher incomes, better eviction prevention tools, and increased public investment in housing all have a role to play in improving affordability. But until we confront the root of the issue—the chronic shortage of housing—we will be merely reshuffling the pieces of a broken system.

If Knoxville wants a strong and growing economy, we need more housing. That requires modernizing outdated regulations and overcoming the resistance to change that has stalled progress for too long. Abundant, affordable housing isn’t a dream—it’s a policy choice. And the five zoning reforms outlined above are just a starting point.

We owe it to the next generation to say “yes” more often. Yes to new neighbors. Yes to more homes. Yes to a Knoxville that grows—not just in size, but in spirit.