What’s Being Built in Knoxville—and Why

A closer look at Knox County's new construction market and how market forces and government regulation are shaping housing trends across the region.

Over the past decade, Knoxville has undergone a remarkable transformation—evolving from a quiet, mid-sized market in the foothills of Appalachia into one the nation’s most dynamic housing markets. Once steady and predictable, many Knoxvillians now keenly understand the change that comes with rapid population growth, surging demand, and a skyline with more cranes than ever before.

The migration wave that fueled the housing boom slowed in recent years, but Knoxville remains a popular relocation destination. Drawn by a lower cost of living and a high quality of life—at least relative to larger U.S. cities—newcomers continue to arrive in steady numbers. Knoxville regularly ranks among the nation’s top relocation destinations by companies like PODS and U-Haul.

The wave of growth is real and tangible. New rooftops are appearing in every direction, spilling past county lines and filling once-empty fields with neatly designed subdivisions. Apartment complexes exist on corridors once occupied by one-level strip malls and quiet two-lane roads now funnel traffic to sprawling subdivisions.

None of this growth is happening by chance—it’s a reflection of the Knoxville’s desirability and growing potential as a hub for research and innovation, with strong public-sector anchors like ORNL and UT. People don’t flock to cities with stagnating economies and limited opportunity; they move to places where jobs are available, quality of life is high, and the prospect of upward mobility feels within reach. And Knoxville, at least from an outsider’s perspective, is one of those places.

Against this backdrop, Knoxville’s housing boom is best understood as the product of intersecting market forces, policy choices, and demographic shifts. These dynamics don’t just explain why growth has occurred—they shape what kinds of homes are being built, where new development takes place, and ultimately, who can afford it.

The Rise of New Construction

Much of the national housing conversation focuses on the lack of housing production. Knoxville is not building enough to meet demand either, but it is bucking the national trend to a degree—not by keeping up, but by building more than it once did.

Historically, Knoxville’s population growth was steady but modest. Like most Sunbelt cities, the 2007–2008 financial crisis decimated the local homebuilding industry, driving many smaller builders out of business and pushing skilled trades workers out of the industry for good. In the years that followed, new construction played only a marginal role in Knox County’s housing market.

In 2012, newly built homes accounted for just 7% of all sales, easily overshadowed by existing-home transactions. But by 2024 that share had nearly tripled, with new homes making up almost one in five sales—a more than twofold increase over the past decade.

The increasing prominence of new construction reflects two things at once: the chronic shortage of existing homes and Knoxville’s growing appeal as a market with upside potential. That potential has attracted historic levels of multifamily investment and steadily rising single-family construction. Annual new-home production has climbed from just 422 units in 2012, when the local economy was still struggling to recover from the recession, to more than 1,500 units in 2024 with a median price of around $400,000. Behind this expansion is both a resurgence of local builders and the entry of D.R. Horton—the nation’s largest homebuilder—which entered Knoxville in 2016–2017, according to AEI date.

There has also been notable shifts in affordability. While new homes still sell at a premium, the gap between new and existing home prices is shrinking. From 2016 to 2018, the typical new home in Knox County sold for roughly 30% more than an existing home—a difference of about $70,000. By 2024, that premium had fallen to just 12%, or around $46,000.

The narrowing price gap might seem like progress. But in reality, it is evidence of a market plagued by a chronic undersupply of existing homes, where tight inventory conditions have led existing homes to appreciate more rapidly, especially at the lower end of the market. New homes haven’t gotten much cheaper—existing homes have simply gotten a lot more expensive.

At the same time, true entry-level new construction has all but disappeared. In 2012, about 19% of new homes sold for less than 80% of the county’s overall median sale price. By 2024, that share had dropped to just 7%. Meanwhile, entry-level existing homes appreciated about 13% faster than move-up homes over the past decade. So not only has entry-level construction slowed, many of the homes that once qualified as entry-level no longer meet that definition.

The narrowing price premium and collapse of entry-level home production point to underlying demographic, political, and economic shifts that are pushing builders to pivot toward smaller homes.

New Homes Are Getting Smaller. But Lots Are Getting Larger.

Like in other cities, new homes have been getting smaller over the past few years.

According to data from the American Enterprise Institute, the median gross living area for new homes built in Knox County fell to 2,141 square feet in 2024—down from an average of roughly 2,350 square feet from 2015-2019. At the same time, the average lot size for new homes grew to over 10,000 square feet in 2024, compared to just 8,500–9,000 square feet from 2015–2019.

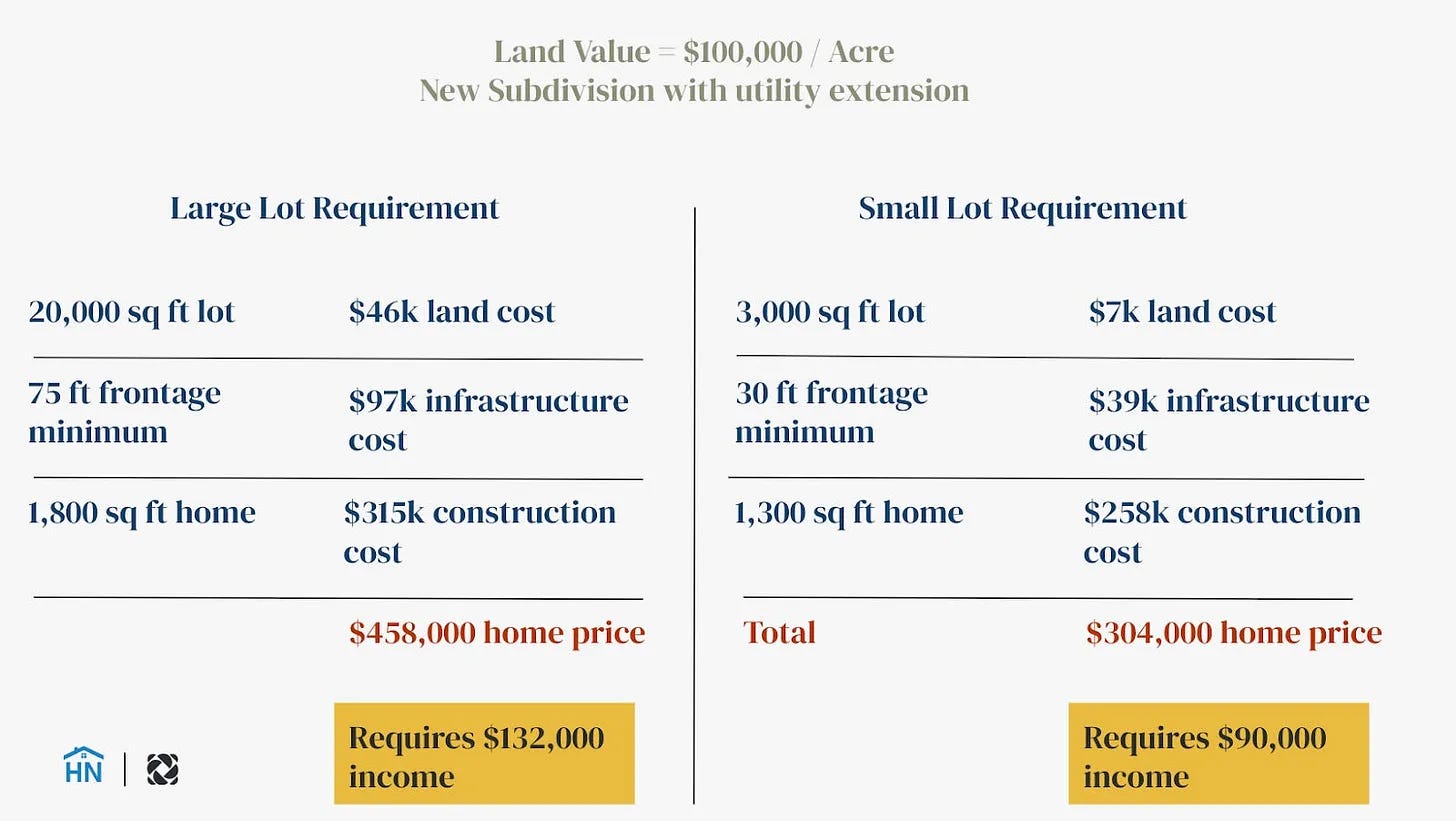

These diverging trends—smaller homes and larger lots—reveal a fundamental disconnect in the U.S. housing market between market forces and the political process that governs development. Together, they offer a clear example of how land use regulations directly shape what kinds of homes get built, and by extension, how much those homes cost.

On the market side, home size is largely determined by demographic and economic trends. Research shows significant pent-up demand for smaller homes, driven both by affordability constraints and shrinking household sizes.

By contrast, lot size is primarily driven by government regulation. It is the product of local zoning and land use regulations—decisions often shaped by political considerations rather than consumer demand.

Understanding these competing dynamics is critical as it demonstrates how regulations can—whether intended or not—undermine affordability, and how the political process around land use often runs counter to what households actually want and need.

Smaller Homes for Smaller Families

Household sizes are shrinking, and an increasing number of individuals choosing to live alone. As of 2023, approximately 30% of households in Knox County consisted of just one person—reflecting a broader shift in household composition across the United States, which has seen its average household size fall from 3.25 to 2.5 over the past fifty years.

The sustained decline in household size, combined with the composition of the existing housing supply, has created a serious mismatch: 66% of households in Knox County consist of 2 people or less, yet only 37% of the region’s housing stock is 2 bedrooms or less.

Further analysis suggests there could be somewhere between 150,000 to 250,000 empty (or underutilized) bedrooms across Knox County, underscoring the scale of mismatch between the size of homes and the families who live in them. Importantly, some of these “empty bedrooms” are likely used as guest bedrooms or office space—especially in the age of remote work—but others are likely sitting empty.

When viewed through the lens of demographics, the trend toward smaller homes in new construction is perfectly logical: smaller families often want or need less space.

Use me as a case study. I live alone in a three-bedroom house—far more space than I needed or wanted. But in the neighborhood where I hoped to live, smaller options were virtually nonexistent. In the end, I had to buy a larger, more expensive home simply because it was the only choice available. I’m fortunate to have had the financial flexibility to absorb the extra cost, but many families can’t afford to pay for space they don’t need.

Affordability, Affordability, Affordability

At first glance, the recent decline in average new-home square footage might reflect a shift in consumer preferences—smaller households choosing smaller homes to match changing lifestyles. But the reality is more nuanced. While smaller households have certainly added to demand, the trend toward smaller homes is driven far more by affordability pressures than by choice.

Many homebuyers aren’t choosing smaller homes because they want less space—they’re settling for what they can afford.

Over the past five years, rising labor and construction costs have made it more expensive to build homes of any size. Builders, particularly in the starter-home market, have responded by trimming square footage to keep overall prices within reach of buyers.

At the same time, shifting political attitudes about growth and how to accommodate it have exacerbated the problem. Local policymakers, facing growth pressures and neighborhood resistance to density, have increasingly required larger minimum lot sizes. This increases the amount of land required for each home, driving up overall land costs and further squeezing builders’ margins. To offset higher land costs while keeping prices relatively affordable, builders must cut home sizes even more.

The result is a housing market shaped less by consumer preference than by economic and political constraints. Buyers may seem to be choosing smaller homes, but in reality they are navigating limited options created by rising construction costs, escalating land prices, and regulations that mandate larger lots. The homes being built are not simply the product of what consumers want, but of what builders can deliver within these bounds. In this light, the trend toward smaller homes is not a reflection of changing preferences, but an unintended byproduct of economic pressures and political decisions—an affordability squeeze reshaping the new-home market regardless of what consumers would truly prefer.

As is often the case, understanding the housing market means recognizing that two seemingly contradictory facts can both be true: smaller households have boosted demand for smaller homes, but affordability remains the dominant force driving this shift.

Conclusion

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: what’s being built in Knoxville today is not simply a reflection of consumer demand—it’s a reflection of the policies we adopt and the incentives they create. Rising prices, shifting preferences, and evolving demographics all play a role, but so too do zoning regulations, permitting processes, and political choices about where and how growth should happen.

As Knoxville continues to grow, its ability to meet the housing needs of current and future residents will depend on our ability to align policy choices with the market forces that ultimately shape the housing supply. To make that happen, we need political leaders willing to embrace a systemic, data-driven approach that prioritizes our region’s long-term housing needs—not just today’s grievances.

Because in the end, the homes we build—how big they are, where they go, and how much they cost—will shape the trajectory of Knoxville’s future.