How the Politics of Growth Transcend the Left–Right Divide

Zoning and development debates are fueling a political realignment, creating intraparty divides and challenging ideological orthodoxies.

Each time a new housing development is proposed, residents pack meeting rooms—not to oppose growth in general, but to reject a particular development in a particular place. Sit through a few local planning or city council meetings and you'll quickly recognize a common refrain: "I’m not against development, but..."

Over the last decade, residents in rural and suburban communities alike have grown increasingly divided on questions of how and where growth and development should occur.

Opinion polling shows an overwhelming share of Americans believe housing is too expensive and too scarce. In a 2024 Pew Research Center survey, 69% of Americans reported being “very concerned” about the cost of housing, and a staggering 90% said they support building more single-family houses, with 81% supporting such developments in their local areas.

And yet, that consensus seems to vanish when theoretical support meets hyper-local reality. Despite growing concern about housing affordability, Americans are nonetheless broadly supportive of policies that have the practical impact of limiting new construction. A 2023 poll found that 58% of Americans supported giving residents veto power over new developments, while only 32% favored removing regulations and codes that prevent developers from building more housing.

This tension is nothing new. In fact, the roots of our current housing challenges stretch back decades. In the postwar era, federal housing policy explicitly promoted suburban expansion through mortgage subsidies, highway construction, and zoning laws that prioritized single-family homes over other housing types. These policies helped build the American middle class—but they also segregated it economically, and entrenched a suburban development pattern that is now embedded in the American psyche.

Starting in the 1970s, as cities grappled with inflation, disinvestment, and political unrest, many communities turned inward. Growth was no longer something to be welcomed, but something to be controlled. Local governments layered on new zoning restrictions, downzoned large swaths of land, and created permitting processes that empowered vocal opposition. The idea of neighborhood “character” became a political force, often used to justify blocking new housing, especially multifamily or affordable projects.

Today, the consequences of these policies are everywhere. We have a national shortage of millions of homes, especially in high-opportunity areas where people most want to live. Even in fast-growing Sun Belt cities like Knoxville, where developable land is more plentiful, restrictive land use policies have constrained housing supply, driving up costs and pushing working families farther out into the suburbs and surrounding counties.

What is striking, if not unusual, about Americans’ views about growth is the absence of a clear partisan divide—at least not along the traditional right-left divide.

In many ways, the politics of growth transcends conventional ideological boundaries, and party identification has become virtually meaningless as an indicator of one’s views on issues of growth and development. For instance, polling shows that a plurality of both Republicans and Democrats, 45% and 46% respectively, oppose removing regulations and codes to make it easier to build more housing.

Despite historically favoring less government intervention, Republicans approve of more restrictive government regulation of growth at a higher rate than Democrats. According to a 2023 YouGov survey, Trump voters (71%) were far more likely than Biden voters (58%) to say they support government giving residents veto power over new developments—though notably, a substantial majority of both groups support what is in practice an anti-growth policy.

For Republicans, there is a growing tension between free-market principles and local control, with many Republican voters favoring restrictive policies to slow growth and limit change. For Democrats, there is similar tension—between progressive commitments to affordability and environmental sustainability, and a growth-resistant impulse rooted in fears of gentrification and broader skepticism toward developers.

In both cases, the politics of growth are shaped by internal contradictions. Some Democrats have begun to advocate for deregulation as a means to expand housing supply, even if it means siding with developers they might otherwise distrust. More conservative constituencies, once champions of private property rights and minimal government, now favor heavy-handed land-use controls to control or limit growth. In each case, ideology takes a back seat to outcomes.

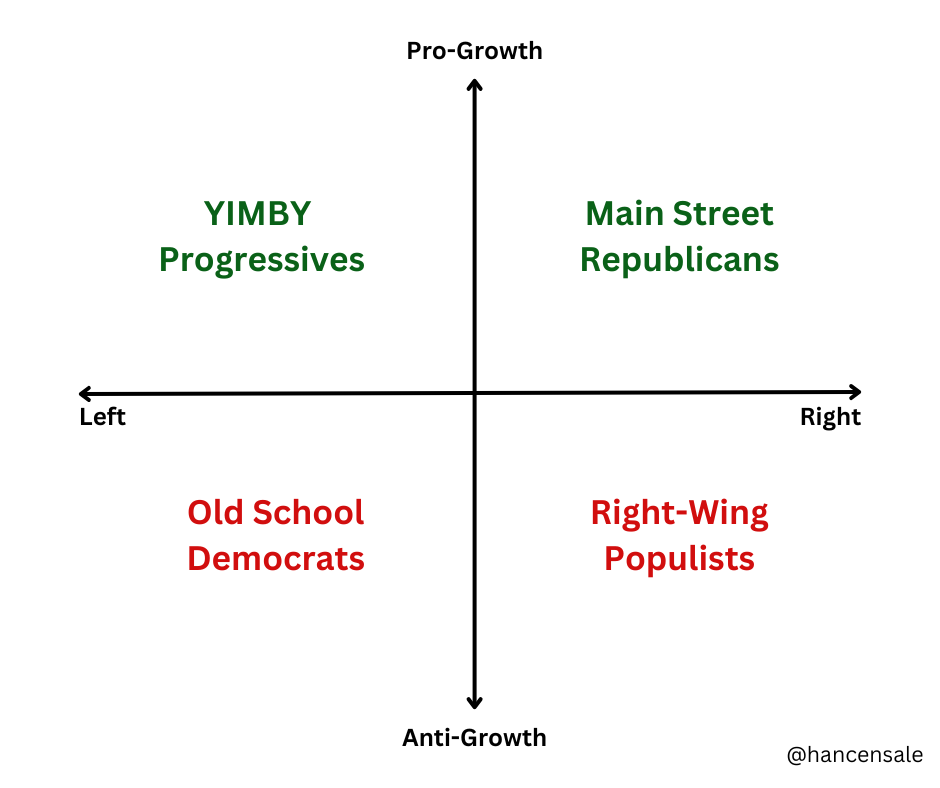

Any attempt to neatly categorize the full spectrum of opinions on growth is bound to fall short—people are simply too varied in their beliefs and motivations. But there are, however, a set of common archetypes that are prevalent enough not to ignore.

These archetypes aren’t defined by party affiliation so much as by geography, socioeconomic status, and proximity to growth itself. Together, they form a messy but revealing picture of how growth is debated in America—not as a simple ideological battle, but as a hyperlocal and often contradictory negotiation over what kind of communities we want to live in.

Over the past decade, four major archetypes have emerged in the conversation about growth: YIMBY Progressives, Main Street Republicans, Old School Democrats, and Right-Wing Populists.

These factions exist in communities across the United States and have upended traditional political alliances. Again, these four archetypes are not comprehensive but they nonetheless provide a framework for understanding the political constituencies driving local decision-making about growth and development.

YIMBY Progressives (Pro-Growth, Left-Leaning)

The YIMBY (“yes in my backyard”) Progressive archetype draws on urbanist traditions that stretch back to Jane Jacobs’ famous 1961 critique, "The Death and Life of Great American Cities," which challenged mid-century zoning orthodoxies and advocated denser, mixed-use urban neighborhoods. Today's YIMBYs view building more housing as a moral imperative—essential to addressing housing affordability, reducing economic inequality, and combating climate change. Though traditionally supportive of government intervention, YIMBY Progressives have come to embrace a deregulatory approach to development and zoning, arguing that overly restrictive land use regulations have exacerbated the housing crisis and encouraged urban sprawl. They often advocate for up-zoning, transit-oriented development, and policies that legalize new types of housing. While generally supportive of pro-growth policies, YIMBY Progressives sometimes embrace overly idealistic proposals that clash with the economic realities of the real estate market.

Main Street Republicans (Pro-Growth, Right-Leaning)

Main Street Republicans follow a long American tradition of viewing development as synonymous with economic growth, opportunity, and prosperity—echoing post-WWII attitudes that led to rapid suburban expansion, highway construction, and industrial growth. Subsequently, Main Street Republicans view increasing the housing supply as an economic imperative—they see development as a driver of job creation, tax base expansion, and overall economic competitiveness. This faction has long favored reducing regulatory barriers and streamlining permitting processes to encourage investment and market-led growth.

Old School Democrats (Anti-Growth, Left-Leaning)

Rooted in the mid-20th century progressive tradition of community planning and activism, Old School Democrats are generally comfortable with government intervention and often emphasize neighborhood preservation and community control. In practice, this often translates into deference to local opposition—empowering neighborhood groups to block or delay development, even when their reasoning is dubious. Often motivated by concerns about gentrification, displacement, and environmental impact, this faction’s support for strict zoning and planning regulations frequently aligns with broader anti-growth outcomes.

Right-Wing Populists (Anti-Growth, Right-Leaning)

Populist conservatives—including many rural and hard-right voters—have embraced zoning laws and development restrictions as tools to resist unwanted change, especially in suburban and rural areas experiencing high in-migration. This marks a sharp departure for a constituency that once decried zoning and its restriction on private property rights as egregious government overreach. Today, this faction favors strict local control, opposes high-density housing, and views new development as a threat to cultural and community identity. Their support for restrictive land use policies often reflects deeper anxieties about rapid demographic, economic, and political change.

These categories aren’t rigid, and many people fall somewhere in between. Still, this simple framework offers a way to better understand the political landscape of housing and development—and the underlying tug-of-war between ideology and outcomes. Across the political spectrum, factions have recalibrated their beliefs to achieve policy goals, underscoring just how complicated and personal this issue has become.

This political realignment helps explain why solving the housing shortage has proven so politically intractable: it is an issue that cuts across traditional partisan lines and scrambles long-standing alliances. It forces unlikely bedfellows into proximity—and yet, too often, just short of cooperation.

The debate over growth—how and where things get built—will always be impassioned. Zoning and land use decisions bring government closest to people's everyday lives, stirring passions and anxieties that don’t fit neatly into left-right politics. Views on development frequently transcend ideology, and it is precisely these unconventional divides that have stalled meaningful action.

It reminds me of the old adage: We agree on the goal, but differ on the path to get there. Yet in today’s climate of distrust and polarization, our ability to build broad, diverse coalitions—once the cornerstone of democratic progress—feels like a relic of a bygone era.

And that’s the root of the gridlock we see today. In a pluralistic democracy, real progress requires coalitions built not just on shared ideology, but on common cause. If we want to address the housing crisis, we’ll need to say yes—not only to growth, but to working with those we don’t always agree with to make it possible.