Against the Death Penalty

On Violence, Fallibility, and the Nature of Justice

“Take out your phone, go to the clock app, and find the stopwatch. Click start. Now watch the seconds as they climb. Three seconds come and go in a blink. At the thirty second mark, your mind starts to wander. One minute passes, and you begin to think that this is taking a long time. Two . . . three . . . . The clock ticks on.

Then, finally, you make it to four minutes.

Hit stop. Now imagine for that entire time, you are suffocating. You want to breathe; you have to breathe. But you are strapped to a gurney with a mask on your face pumping your lungs with nitrogen gas. Your mind knows that the gas will kill you. But your body keeps telling you to breathe.

That is what awaits Anthony Boyd tonight. For two to four minutes, Boyd will remain conscious while the State of Alabama kills him in this way. When the gas starts flowing, he will immediately convulse. He will gasp for air. And he will thrash violently against the restraints holding him in place as he experiences this intense psychological torment until he finally loses consciousness. Just short of twenty minutes later, Boyd will be declared dead.”

—Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissenting, Boyd v. Hamm, October 23, 2025

Last October, the United States Supreme Court turned down a request from an Alabama inmate, Anthony Boyd, to delay his execution for the justices to consider whether killing him by nitrogen hypoxia would violate the Eighth Amendment’s constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Nitrogen hypoxia—an execution method developed in the late 2010s and first authorized by Oklahoma in 2015—kills by forcing a person to inhale pure nitrogen, thereby depriving the body of oxygen. It is, in plainer terms, suffocation.

The case concerned a narrow procedural question—the method by which the state may carry out an execution—not the legality of capital punishment itself. But Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent, in its unflinching account of how a human being would be put to death, elucidates what the law often abstracts away: the death penalty is more than a policy choice or punishment—it is unadulterated violence, meticulously administered by the state. And it brings a broader reality into focus: government-sanctioned execution is not a relic of another era. It remains firmly embedded in the American justice system, still legally authorized in 27 U.S. states.

An Enduring Punishment—and an Unsettled Conscience

To be judged by a tribunal and condemned to death for one’s transgressions has been a fixture of human societies since antiquity and endures today—not just in America but in more than 55 countries across the world. One of humanity’s oldest forms of punishment, the death penalty has long been viewed as a necessary feature of a civilized society, justified by its supporters as a morally proportionate response to the most heinous, morally reprehensible crimes—an affirmation of society’s condemnation of the irreparable harm such crimes impose.

It has not, however, persisted without criticism. One of the earliest and most influential critics, Enlightenment-era philosopher Cesare Beccaria, argued in his 1764 treatise On Crimes and Punishments that executions were neither an effective deterrent nor morally defensible. And since then, prominent historical figures from Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens to Tolstoy, Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela have advocated for the abolition of capital punishment.

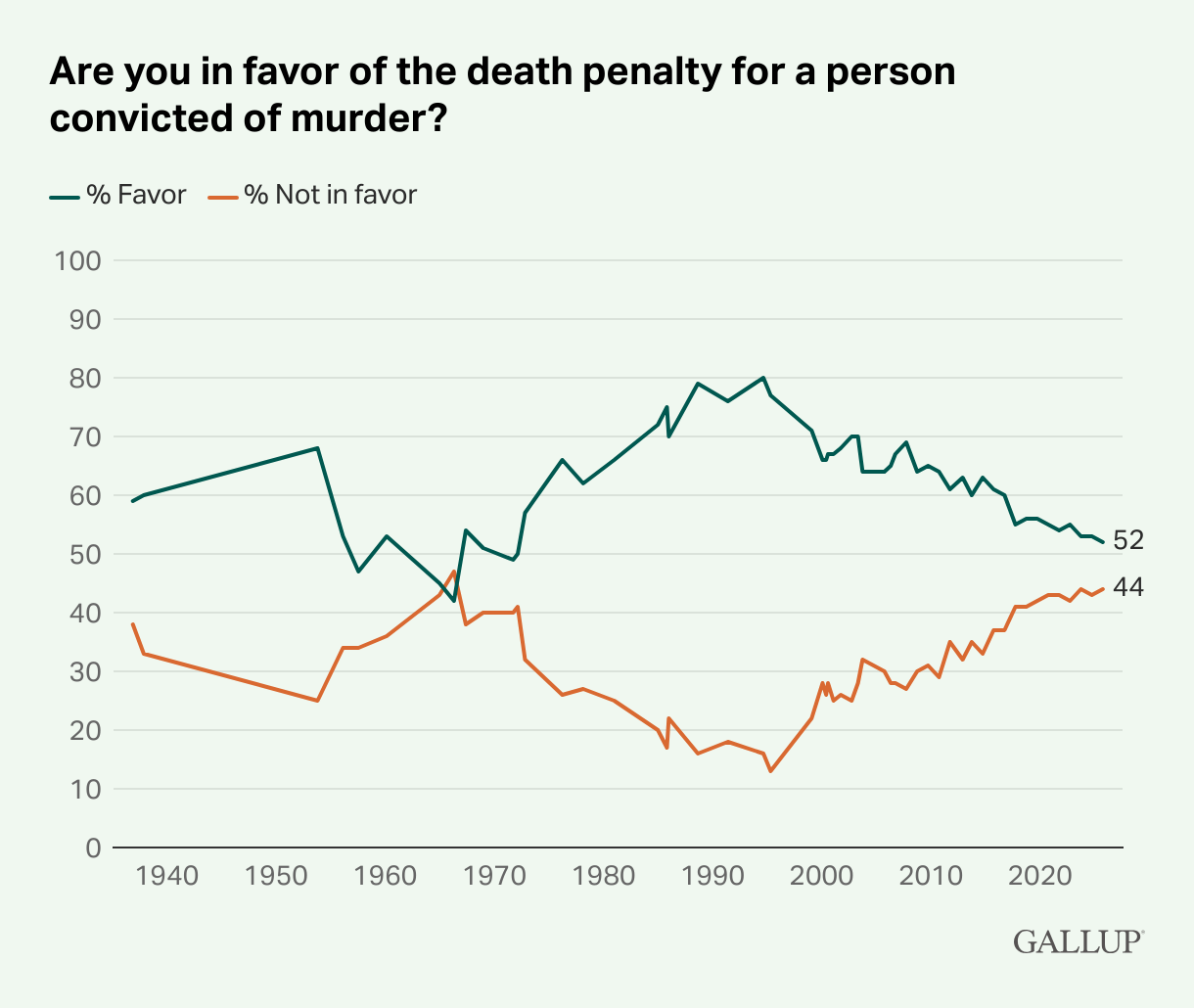

Yet the practice endures, sustained by the slow pace of legal reform and by its appeal to the deeply human impulse for retribution—the desire to balance the scales and to impose finality where lesser punishments seem insufficient. That appeal to deep moral intuitions helps explain why so many Americans still support capital punishment today. Though support has fallen from roughly 80% in the mid-1990s, amid heightened fear of violent crime and a bipartisan “tough on crime” consensus, roughly 50–60% of U.S. adults still favor the death penalty for convicted murderers, as documented in decades of public opinion research by Gallup and the Pew Research Center.

Even still, it is not a position most Americans are especially proud of. Pew’s research also found that capital punishment draws significantly more support online than in telephone surveys—a phenomenon known as social desirability bias, or the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in ways they believe are more socially acceptable as opposed to what they truly believe.

But the question lingers. Why do so many Americans endorse the death penalty in the abstract, yet hesitate to defend it aloud, face to face? Perhaps the beginning of the answer lies in the fact that capital punishment is not simply a matter of policy design and effectiveness. It is an intensely moral question, too—one that uniquely resists compartmentalization. Questions of morality do not hover at the margins of the policy debate; they are embedded within it.

The Cost Consideration

First, there is the simple and dispassionate question of cost. Many proponents of capital punishment emphasize the exorbitant cost of long-term imprisonment, arguing that execution is a fiscally responsible alternative. But scores of studies (see here, here, or here) have affirmed that, for a variety of structural reasons, the death penalty is much costlier than life imprisonment.

Capital cases are, by design, inefficient. Lengthy trials, extended appeals, and special procedures built into death penalty cases make them exceedingly costly. Such procedural safeguards are not bureaucratic excess; they exist because the punishment is irrevocable. The legal system slows itself down precisely because the risk of error is so high. That caution, while necessary, carries an enormous price tag. One widely cited analysis found that each death row inmate costs roughly $1.12 million more (in 2015 dollars) than an inmate serving a comparable life sentence in the general prison population.

The result is a system that pays a premium without reliably delivering what it promises: many individuals sentenced to death are never executed. Instead, after years or decades of litigation, they die of natural causes or have their sentences reduced to life imprisonment—after the state has already incurred the inflated costs unique to capital prosecution.

What makes this arrangement especially difficult to justify is that these inflated costs do not provide much, if any, public benefit. They purchase procedural caution—an acknowledgment, embedded in law, that killing someone in the name of the state demands extraordinary care. That acknowledgment is itself revealing.

The Deterrence Myth

There is also the issue of deterrence. Proponents contend the death penalty prevents crime in the first place. But that argument has withered underneath decades of research that has found no credible evidence the death penalty reduces violent crime. States without capital punishment consistently record violent crime rates equal to—or lower than—states that retain it.

That isn’t exactly surprising. The deterrence theory assumes a level of calculation and levelheadedness that rarely exists in moments of extreme violence. Most homicides are crimes of passion or desperation, committed impulsively, under the influence of drugs or alcohol, during domestic disputes, or amid mental health crises—conditions in which distant legal consequences exert little influence over decision making. The marginal difference between life imprisonment and death is not something most offenders meaningfully weigh before acting—the certainty of punishment matters far more than its severity.

Nor does the death penalty deliver deterrence through visibility or speed. Executions are rare, delayed, and legally obscured by years—often decades—of appeals. Whatever symbolic force they might carry is diluted by time, distance, and procedural complexity. A punishment so infrequently and unevenly applied cannot plausibly serve as a general warning to society at large.

What is striking is that this conclusion—that the death penalty does not deter crime—is not all that controversial. Americans across ideological lines have absorbed and accepted the evidence. According to Pew Research, more than six-in-ten Americans, including about half of those who support the death penalty, say it does not deter people from committing serious crimes.

If deterrence is the goal, capital punishment has proven an abject failure.

The Fallibility Dilemma

Then, there is the matter of error. In a system built by humans, certainty is always borrowed—temporary, contingent, subject to error and to time. The American criminal justice system is no different. It is fallible, prone to error even in the surest of circumstances.

Some argue that advances in modern forensics and the burden of proof are so high as to make concern about the potential for error unnecessary. On its face, such a position is not entirely implausible. But it does not withstand empirical scrutiny. Since 1973, over 200 people sentenced to death were later exonerated. That figure may be small compared to the thousands who have faced capital charges, but it is not an abstraction. It represents hundreds of individuals who stood on the brink of death on account of crimes they did not commit.

A system that can take life cannot allow for error—and yet errors happen because the American justice system, for all its virtues, cannot escape human fallibility.

Courts are not sanctuaries. They are human institutions, governed by rules and staffed by people operating under pressure and constraint: police departments under pressure to clear cases; prosecutors operating under professional incentives that, implicitly or explicitly, place weight on convictions; defense attorneys stretched too thin; jurors asked to compress an entire life into a verdict after days of testimony; judges bound by procedures that are necessary, though sometimes merciless. Even when each actor proceeds in good faith and performs their task honorably and with rigor, the system remains what it is—human, fallible, and therefore vulnerable to haste, bias, misjudgment, and chance.

The death penalty demands something more than competence; it demands near-omniscience. Not merely that the facts were right, but that everything was right—the identification, the timeline, the science, the confessions, the incentives, the witnesses, the undisclosed evidence, the defendant’s mental state, even the meaning of “beyond a reasonable doubt” in the minds of twelve jurors. And it demands that we get everything right not just once, but reliably—across decades, across counties, across election cycles, across the uneven pursuit of capital prosecution, across changing forensic standards.

That is the certainty capital punishment requires, and it is not a certainty human institutions can honestly promise.

The Ritual Beneath the Law

The French-Algerian philosopher and novelist Albert Camus, in his 1957 essay Reflections on the Guillotine (link), lays bare the brutality of execution in a way that stirs the same moral unease provoked by Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent.

Shortly after World War I, Camus recounts, his father attended the execution of a man convicted of murdering a family of farmers, including multiple children, in Algiers. Deeply appalled by the killing of children, his father vowed to attend the execution expecting the grim reassurance of justice carried out. Instead, he returned home shaken, compulsively vomiting, and unable to eat. “He had just discovered the reality hidden under the noble phrases with which it was masked,” Camus writes. “Instead of thinking of the slaughtered children, he could think of nothing but that quivering body that had just been dropped onto a board to have its head cut off.”

That single morning, Camus writes, transformed his father’s view of capital punishment. The execution did not restore order or affirm the rule of law; it revealed something far more disturbing. Stripped of legal ritual and civic justification, the execution appeared for what it was: a deliberate, intimate act of violence, administered by the state. Camus does not argue in terms of theory or statistics. He insists instead on confronting the reality the law and its legalese can obscure—that capital punishment is not an idea or a deterrent, but a human body destroyed in the name of justice.

“When the extreme penalty simply causes vomiting on the part of the respectable citizen it is supposed to protect, how can anyone maintain that it is likely, as it ought to be, to bring more peace and order into the community?” Camus continues. “Rather, it is obviously no less repulsive than the crime, and this new murder, far from making amends for the harm done to the social body, adds a new blot to the first one.”

Indeed, capital punishment is best understood exactly as Camus conceived of it: ritualistic violence. The death penalty claims to achieve closure and finality—some moral balancing of the ledger. But violence does not launder violence; it only changes who gets to call it lawful. An execution does not resurrect the victim. It does not unbreak the family. It does not undo the years of fear or grief or absence. What it can do—what it often does—is extend the life of the crime, keeping it on a procedural ventilator through appeals, hearings, headlines, and anniversaries. The state offers “closure” and delivers a second, slower trauma: a long public countdown that forces families to rehearse the worst day of their lives again and again, until the killing is carried out in their name.

The death penalty, then, amounts to the chasing of an illusion. It chases epistemic certainty in a world that cannot supply it. It chases moral finality in a world where nothing that matters is ever that clean. It pretends we can perfect what is, at best, a managed imperfection—and that we can heal loss with another death.

In Support Of Life Without Parole

The truest mark of humility in justice is to recognize the limits of what we can know and what we can repair. A restrained society punishes decisively and protects the public—without making a sacrament out of killing, and without claiming a godlike certainty it does not, and cannot, possess.

Life without parole offers a more restrained moral posture—one that also achieves every legitimate aim of punishment. It is severe and permanent, yet restrained. It punishes without spectacle, incapacitates without imitation, and upholds an ideal that justice is about protecting the future rather than reenacting the past. It insists on accountability while refusing to surrender to vengeance. It affirms that even those who have committed the worst crimes imaginable remain human beings—culpable, dangerous, deserving of harsh punishment, but not inhuman. And crucially, it preserves the possibility, however rare, of correcting a wrongful conviction.

In a system created by human hands, wielding imperfect institutions, the death penalty asks for a certainty we do not possess in pursuit of an end we cannot achieve. Life without parole better balances our moral foundations. It protects society, ensures those who commit the gravest crimes never walk free, and avoids the irreversible injustice of wrongful execution. The death penalty may satisfy a visceral desire for retribution, but in practice—and in conscience—it asks the state, and its people, to claim a moral authority it cannot safely hold.

In the end, justice is not diminished by restraint; it finds its truest expression there.

Following the Supreme Court’s denial of a stay, the State of Alabama executed Mr. Boyd, 54, by nitrogen suffocation on October 23, 2025—the first execution in U.S. history using nitrogen hypoxia. What followed closely resembled the scenario Justice Sonia Sotomayor had warned of in dissent. Witnesses reported that nitrogen began flowing shortly after 5:55 p.m. By 5:57 p.m., Boyd’s body began reacting forcefully, straining against its restraints as his eyes rolled back and his legs lifted from the gurney. By 6:00 p.m., the convulsions had slowed, but they were replaced by prolonged, labored breathing that continued for more than fifteen minutes, each breath visibly shaking his restrained head and neck. At 6:16 p.m., Boyd was still taking deep breaths before becoming motionless several minutes later. State officials pronounced him dead at 6:33 p.m.—more than thirty-five minutes after the nitrogen gas was first administered.

I have slowly changed my stance on this issue over the past several years. Once a staunch supporter of the death penalty today I would vote to abolish it for many of the reasons you cited. It is not a deterrent to crime, it costs more to house and accommodate death row inmates and is simply incompatible with the values of a civilized society. I’ve come to this conclusion thoughtfully, prayerfully and civility debating with friends. Thanks for writing this article. I still challenge myself to reconsider but you have affirmed many of my convictions. Thanks Hancen.